1999 Schriftbilder Catalogue of images /

Catalogue d’images

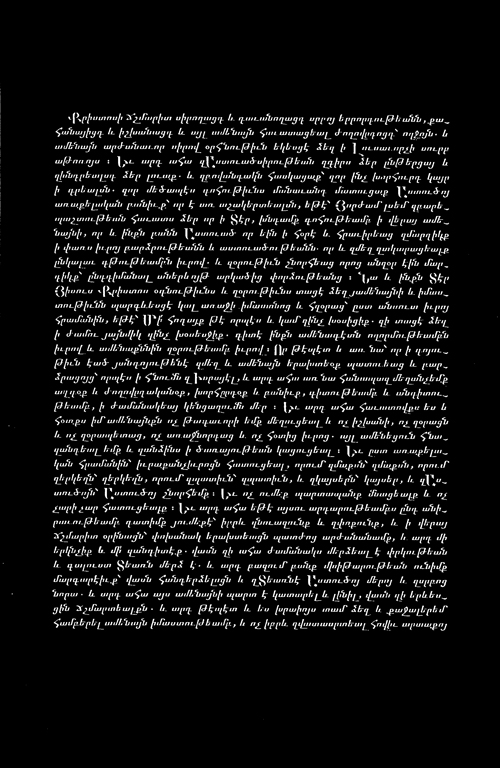

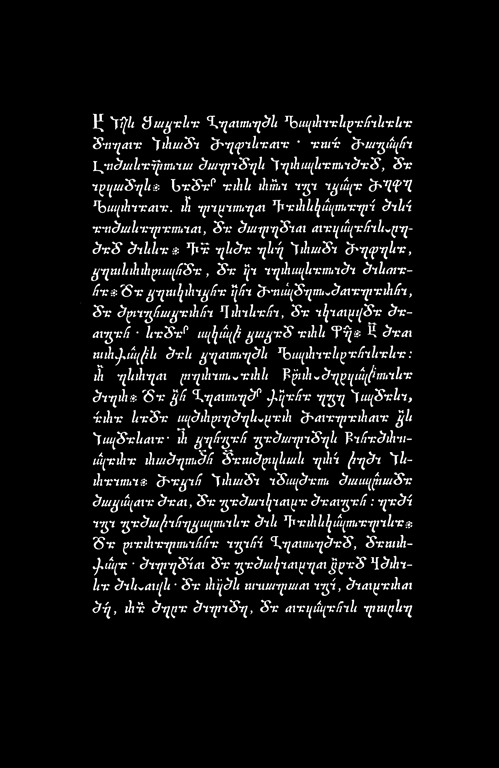

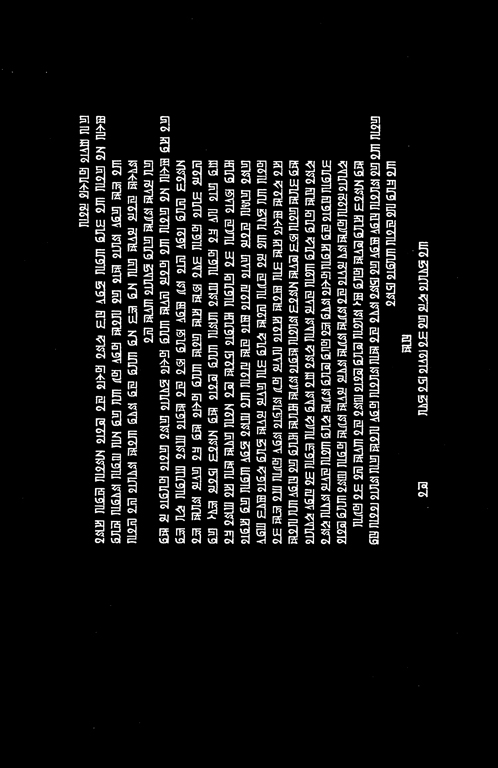

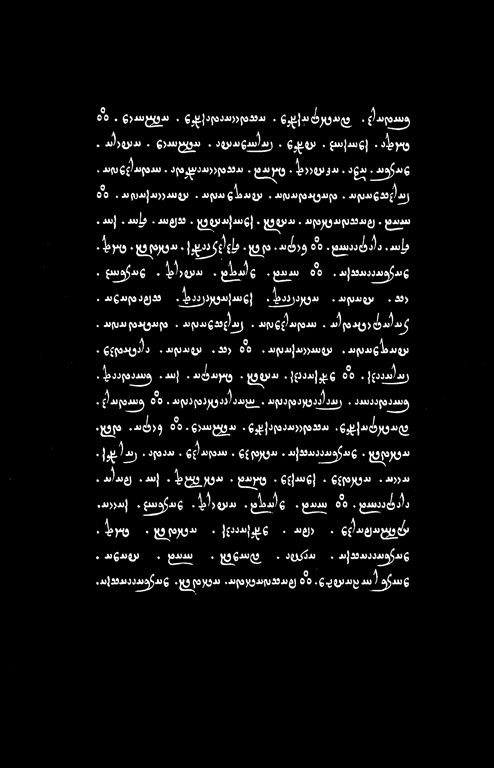

Armenian, 1999

The Armenian alphabet was created in or about a.d. 406, by St. Mesrop (the ‘saint’), a monk, in collaboration with St. Sahak, supreme head of the Armenian Church, and a Greek from Samosata called Rufanos. It was better suited to the phonetically complex Armenian speech than an earlier attempt to adapt the Greek alphabet. However the Greek influence was recognizable in the creation of vowels, the direction of writing and the upright, regular position, while St. Mesrop was credited with the creation of the consonants.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

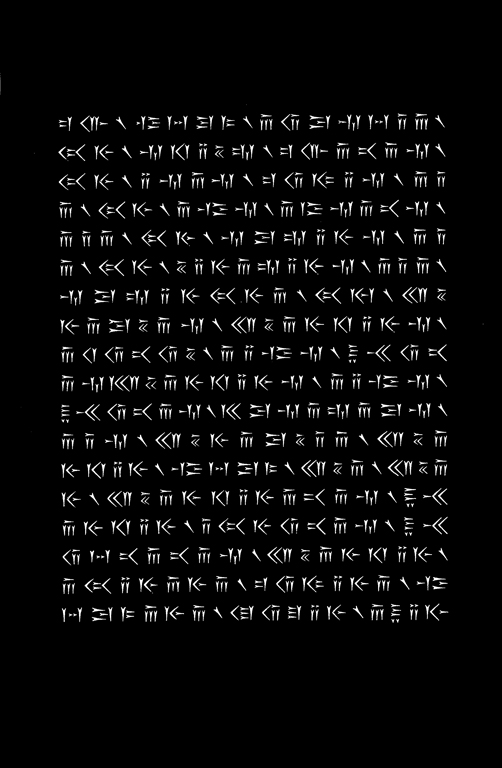

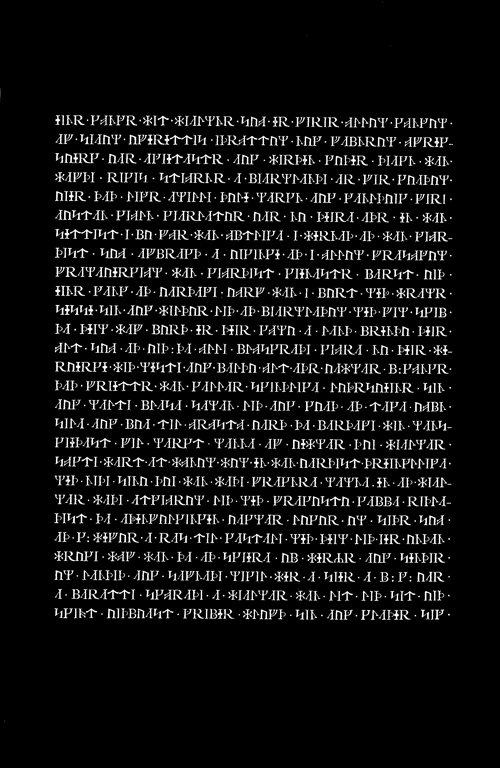

Babylonian, 1999

The origins of the Babylonian cuneiforms remains uncertain, but from the trilingual inscriptions found in the ruins of Persepolis (Rock of Behistun) it was discovered that three forms of writings, all cuneiforms, represented three different languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian or (Semitic) Akkadian as it was also called.

An adaptation of the Babylonian, the Persian cuneiform, became the official script of the Persian Archaemenid dynasty (VI – IV century b.c.) and was used to transcribe Old Persian.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

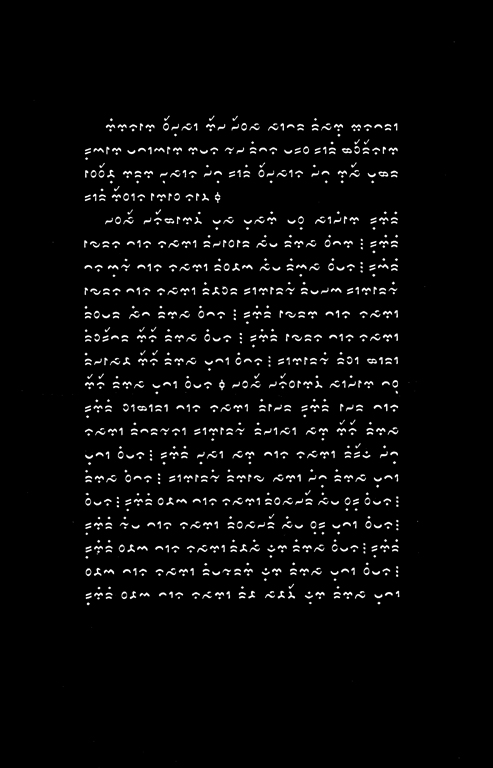

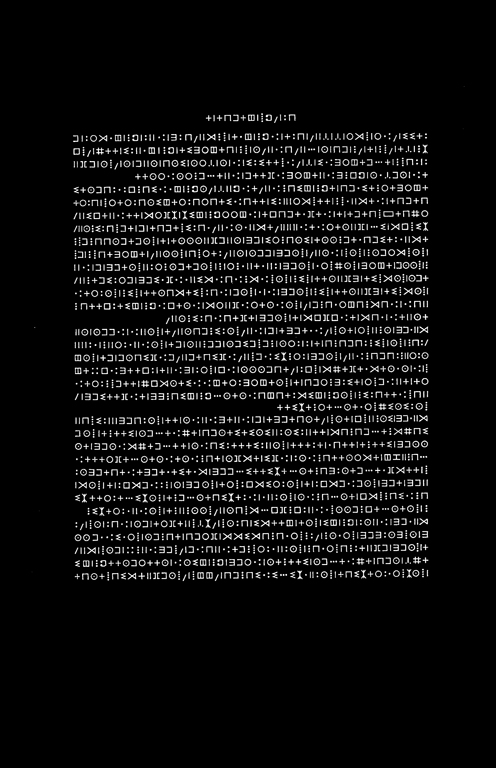

Bugis, 1999

This Austronesian language is spoken by one of the two major tribes of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi formerly called Celebes, the Macassarese and Buginese. The Bugis character was cut by Marcellin Legrand under the direction of Edouard Dulaurier in 1841, and was first used in the Collection des lois maritimes antérieures au XVIIIe siècle, by J.-M. Pardessus, Volume VI, p. 467 and following, Paris, 1845.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

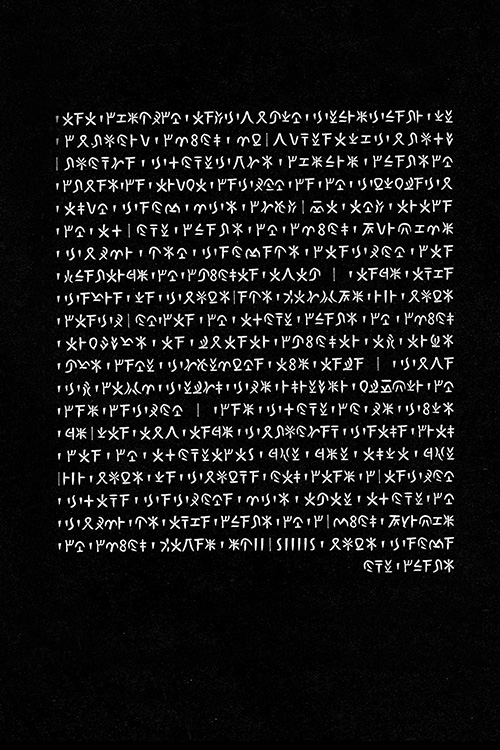

Estranghelo, 1999

The term Estranghelo was possibly derived from satar angelo, the ‘evangelical’ writing or from the Greek strongyle, the ‘round script.’ It is an archaic form of the Syriac alphabet and as such was used to write the sacred books of the Syrian Christians.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Cypriote (Cyprian), 1999

The origin of the Cypriote script has been subject to much controversy, but it is now generally accepted that it was derived from the Cretian linear script, and it is considered the purest of syllabic writing of the Old World. The earliest example of writing found on the island of Cyprus is a linear inscription on the handle of a pitcher, attributed to the Period III of the Early Bronze Age: ca. 2400–2100 b.c. The direction of writing is generally from right to left, but sometimes it is left to right or boustrophedon (lines alternating, right to left and then left to right).

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Georgian Ecclesiastic Script, 1999

The earliest Georgian inscriptions date back to the fifth century a.d., and the earliest manuscripts to the eighth century a.d. The origin of Georgian writing and the connection between its two main varieties – Khutsuri, the ecclesiastical writing, and Mkhedruli, the military ‘lay’ writing – is still uncertain. Traditionally the former is considered a creation of St. Mesrop, parallel to that of Armenian writing, but many influences have been identified, including Greek, Latin, Persian, Arabic, Turkish and others.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

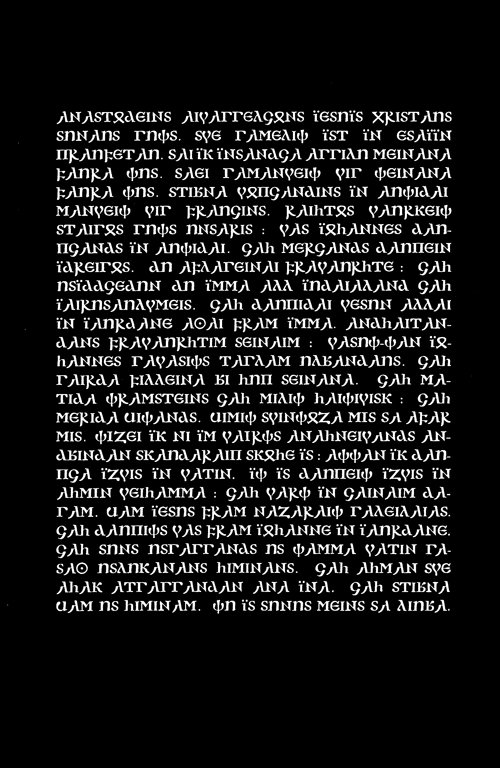

Gothic, 1999

Bishop Wulfila translated the Bible into Gothic, a language spoken by a Germanic people who, during the fourth century, lived in what is now Bulgaria. The Goths or rather Visigoths, or Western Goths, were the first Germanic people to be converted to Christianity. Wulfila employed an alphabet that he invented, generally known as Gothic, which consisted of Greek as well as Latin characters, with additional signs freely invented or borrowed from Runes.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

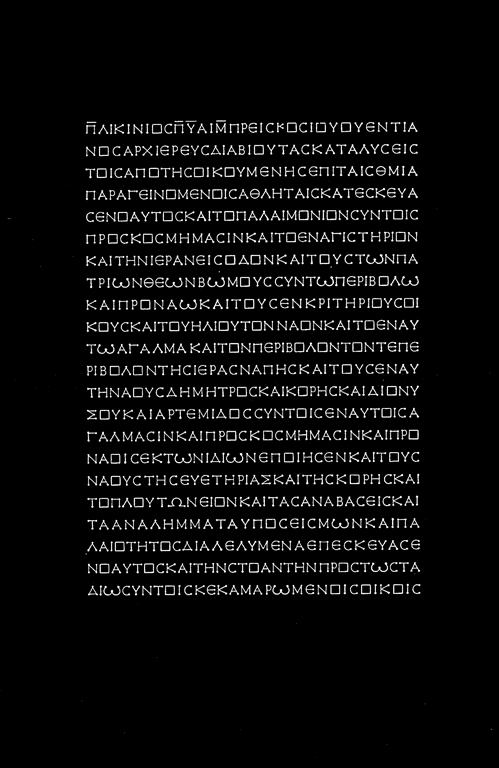

Greek Inscription, 1999

In about the eighth century b.c., the Greek language could not be transcribed in any of the existing alphabetic systems. The Greeks therefore had the idea to borrow certain consonants from the Aramaic alphabet that did not exist in Greek, and to use them to transcribe their vowel sounds. So we find A (alpha), E (epsilon), O (omicron), and Y (upsilon). I (iota) was an innovation. By the fifth century b.c., the alphabet consisted of twenty-four signs or letters, of which seven were vowels; it could be written in either uppercase (capital) or lowercase letters. The classical alphabet was always retained as a monumental script and for capital letters in manuscripts. However, more cursive forms developed from the classical alphabet, were employed in writing on parchment, papyrus and wax tablets.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Hebrew, 1999

It is believed that the early Hebrew alphabet was superseded by the Aramaic alphabet during the Babylonian exile. The Aramaic script is therefore the parent of the ‘square Hebrew’, the modern Hebrew alphabet. Four types of the modern Hebrew alphabet can be traced: The square script which developed into the neat, well proportioned printing type of modern Hebrew. The medieval formal styles. The rabbinic, employed mainly by medieval Jewish savants, and also known as Rashi-writing; and The cursive script, which gave rise to many local varieties in the Levant, Morocco, Spain, Italy and other countries, of which the Polish-German form became the current Hebrew cursive script. This division must be very old, for it appears in fragments of the seventh and eighth centuries a.d. “Modern Hebrew is actually not much older than its (Israel’s) own oldest speakers. While the language of the Bible was indeed the common language of prayer and study for the dispersed Jewish communities, it had not been spoken for 1,800 years. Today, the language is still being shaped to serve contemporary needs. The whole country is a kind of language laboratory.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

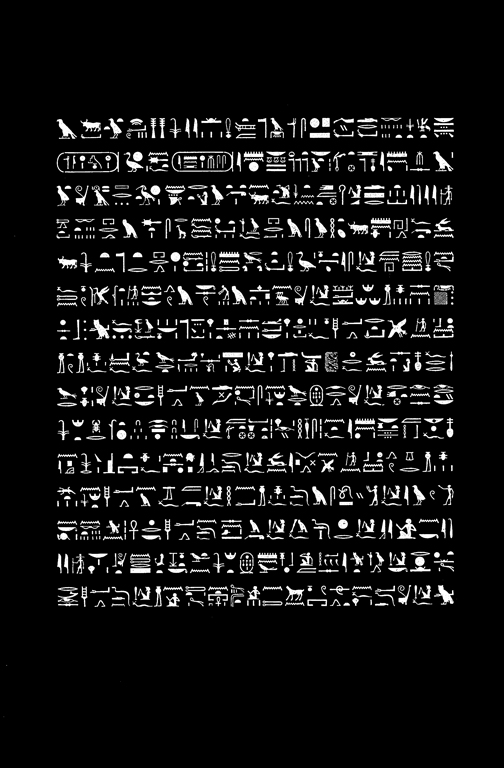

Hieroglyphic, 1999

The word “hieroglyph,” used in the writing of the ancient Egyptians, means “writing of the gods.” The earliest known hieroglyphic inscriptions date back to the third millennium b.c., but the script must have originated well before that. It underwent no major changes until a.d. 390, when Egypt was under the domination of Rome. Over the centuries the number of signs increased from approximately seven hundred to around five thousand. The writing system is made up of three kinds of signs: pictograms, stylized drawings that represent objects or beings, with combinations of the same signs to express ideas; phonograms, the same or different forms used to represent sounds; and determinatives, signs used to indicate which category of objects or beings is in question.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

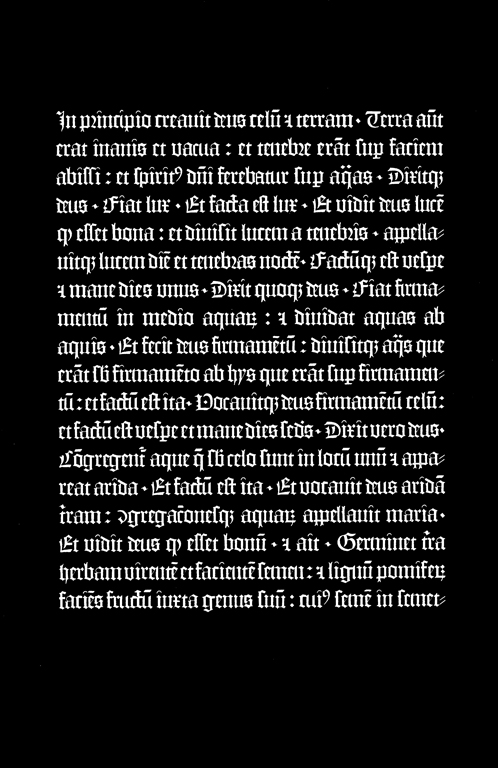

Latin in Gothic Print, 1999

It is not known for certain whether Gutenberg was solely responsible for the printing of his first ever Latin Bible in 1450. This Bible is still heavily influenced by the medieval spirit; it is richly illuminated and uses Gothic characters. It is known as the Thirty-Six Line Bible (there were 36 lines per columns) to distinguish it from the 642-page called Mazarin Bible, printed in 1455, which had forty-two lines per column. Initially, printing appeared as an extension of handwriting, not the revolutionary change that we now know the advent of printing represents. The printer’s main goal was to rival the scribe and to succeed in producing volumes that were as luxurious as the calligrapher’s works. Scribes or copyists tended towards the use of letterforms of German provenance, called Gothic. The Gothic characters were narrower than the Carolingian (another character commonly used at the time).

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Collection:

The Donavan Collection, University of St-Michael’s College,

Toronto

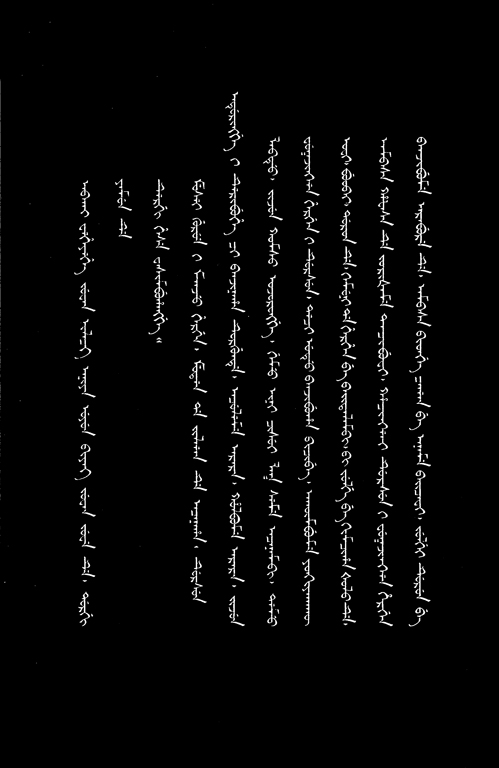

Manchu,1999

Originally the Manchu script was a mere adaptation of the Mongolian alphabet to the Manchu tongue. In 1748, the Manchu script was revised by the Manchu emperor of China, Ch’ien-lung, who according to tradition chose one form of the thirty-two existing variants. Manchu is written like Mongolian, in vertical columns running from left to right.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

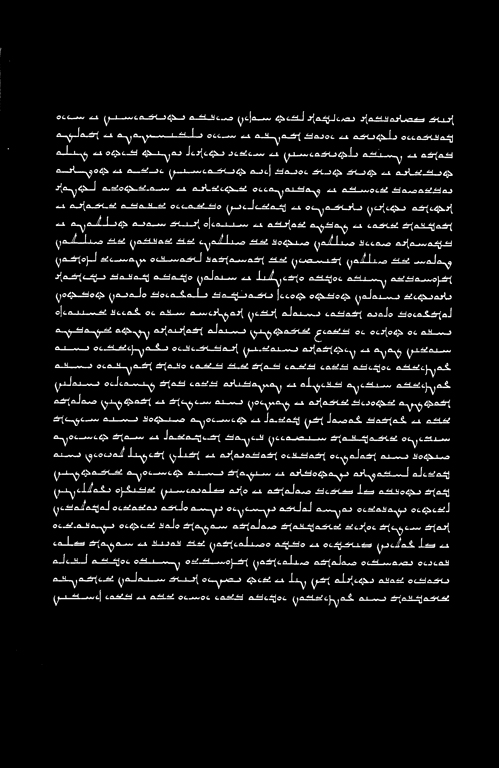

Mandæan, 1999

The Mandæans are a gnostic pagan-Jewish-Christian sect of probably Syrian origin who were settled in Mesopotamia since ancient times (ca. fifth century a.d.). The Mandæan speech, highly symbolic and archaic, is an eastern Aramaic dialect closely related to Babylonian Aramaic but influenced by the neighbouring Persian and Arabic languages and dialects. The Mandæans looked upon their alphabet as magic and sacred and their chief work is the post-Islamic Book of Adam (also called Ginzâ, ‘treasure,’ or Sidra rabba, the ‘Great Book’). The first edition of the Islamic Book of Adam was printed in London in 1815 in its Syriac transcription. The Imprimerie Nationale remains the only institution to possess the Mandæan characters since 1892. The Mandæans are almost extinct; a 1932 census counts 4,805.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Nägarï, 1999

Nägarï or Deva-nagari, as it is also called, is considered the most important Indian script, the script of the educated classes. Its history is mainly connected to that of Sanskrit, the sacred language of the Brahmans, which for many centuries was the exclusive literary language of northern India. The Deva-nagari character – of which there are two varieties, the eastern and the western – was never employed in daily life, and its earliest manifestations belong to the seventh and eighth century a.d. It remained unaltered for many centuries and was eventually replaced after the Moslem conquest of the Punjab and subsequent political changes, which brought neo-Persian script and language into use.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

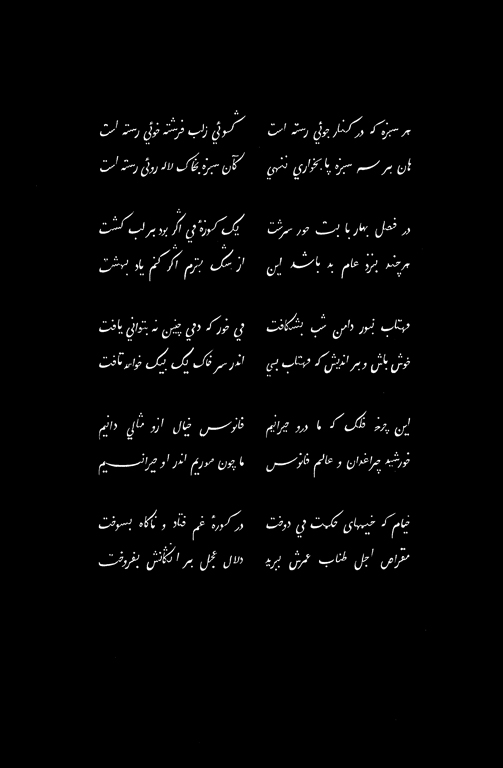

Persian, 1999

Persian is an Indo-European language belonging to the same group as Latin and French and has nothing in common with Arabic, which is a Semitic language. However, like the Turks, the Persians took their writing script from the early Arabic script and adapted it to their needs. The use of Arabic script was even more widespread than that of the spoken language. Areas as far apart as North Africa, Asia Minor, India and parts of China were all subject to the Islamic conquest and all came to adopt its writing system. For Muslims, writing has a sacred character. The

prophet Mohammed is believed to have recorded the word of Allah directly, with no intermediary. In contrast to Persian manuscript, where people are depicted, the representation of Allah and Mohammed is forbidden for Muslims.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Phagspa, 1999

A Mongolian script and part of the Altaic linguistic family, the Phagspa was adapted from Tibetan (square script) writing, and adopted to Mongolian speech in 1272 by the Grand Lama of Sa-skya by invitation of the Great Qubilay Khan. It was replaced by another script in 1310, but is said to have been used until the end of the Mongolian dynasty around 1368.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Runic, 1999

Runes were magical characters or signs and symbols (Zeit- und Zauberzeichen) that were used in different Germano-European areas before Christianization and the introduction of the Latin alphabet. The Germanic term runo (or runa) signifies “secret,” and as some signs have been found scratched onto weapons or jewelry, Runes were believed to have magical powers capable to ward off evil. They were also associated with the notion of time, such as the 24 gothic Runes which were said to be the equivalent to the 24 hours in a day. Finally, the study of Runes was mostly attributed to priests and women.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Sumerian (Ninivite), 1999

The Sumerians are the first known users of cuneiform writing. It is unknown, however, whether the Sumerians are the actual inventors of this form of writing, but they represented the dominant group of the Near East for more that 1500 years – i.e. from the late fourth millennium until the first centuries of the second millennium b.c., in which period they produced a vast and highly developed literature, consisting of myths, hymns and epics. Several thousands of tablets and fragments containing literary compositions, mainly of the period around 2000 b.c. have so far been discovered.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Tibetan, 1999

It is generally accepted that the Tibetan script was invented, or rather revised from an older script in use in Tibet, in a.d. 639 by Thon-mi-Sam-bhota, minister of the great king Srong-btan- Sgam-po, who founded the state of Tibet. The Tibetan language is a member of the Tibeto-Burmese subfamily of the Sino-Tibetan language group. The earliest extant Tibetan literature belongs to the seventh century a.d. It consists mainly of translations of Sanskrit books, and these translations not only transformed Tibetan speech into a literary language, but in many cases preserved works which had been lost in their original form.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Tifinag, 1999

The origins of the Tamachek script is still uncertain. Early Lybian writing however, used by the ancestors of the Berbers is usually thought to be the prototype of the Tamachek writing of which the character is called by the natives Tifinagh, and which is still in use today among the Tuareg of north-west Africa. Using the Tifinag typeface cut in 1858 by Bertrand Loeulliet, A. Hanoteau’s Essai de grammaire de la langue tamacheq was printed by the Imprimerie Impériale in 1860.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

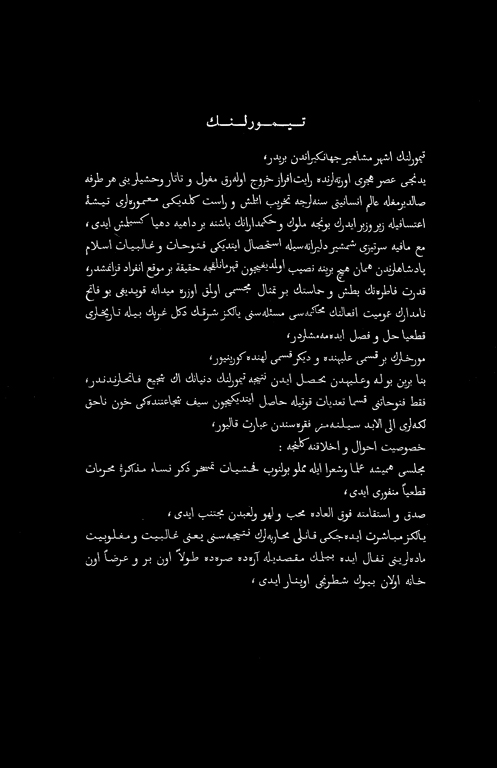

Turkish (Arabic Alphabet), 1999

The first writing the Turks employed originated in Central Asia. It is a runic alphabet, derived from the Aramaic, which evolved into Arabic writing and is known to us through inscriptions on steles and fragments of manuscripts. This Arabic alphabet was adopted for and adapted to Osmali Turkish, which, as the official language of the Ottoman Empire, became most widespread and the most literary of all the Turkish forms of speech. The Arabic alphabet remained officially in use until 1929, when Mustafa Kemal Pas (the Atatürk), first president of the Republic, replaced the Arabic character with the ‘new’, i.e. ‘Latin’ character.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Zend Avesta, 1999

The most famous of the Persian indigenous scripts, the Avesta alphabet was the script of the sacred writings and literature of the Parsees, descendants of those Persians that fled to India in the seventh and eighth centuries to escape Muslim persecution, and who still retain their religion, Zoroastrianism. According to Parsees, ‘nothing which was not written in this (Avesta) dialect can claim to be considered as part of the sacred literature.’

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)

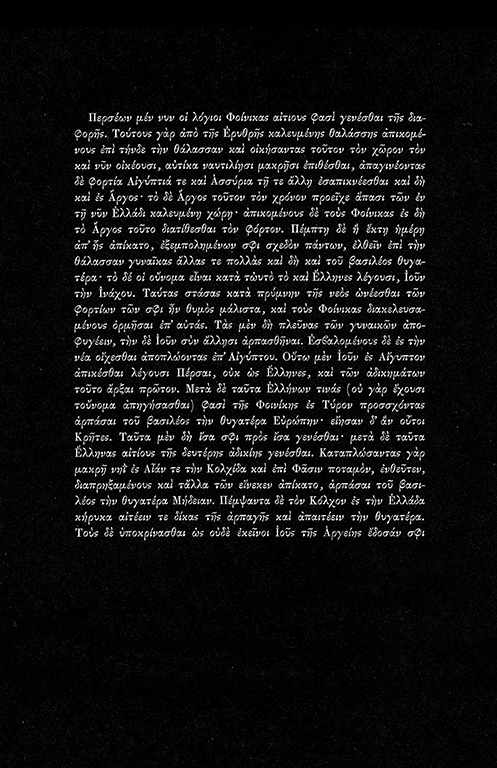

Ancient Greek, 1999

The medieval form of Greek writing evolved into a script used for printing, which was based on the lowercase writing in use since the development of the Greek alphabet.

—

From a series of 23 photograms

of text pages of dead scripts and languages / Détail d’une série de 23 photogrammes de pavés de texte de scripts et langues mortes.

Gelatin silver print / épreuve à la gélatine argentique

16 x 20 inches / pouce

(50.8 x 40.6 cm)